Trusting in the experiences and knowledge that I acquired over seven months of volunteering in the Philippines, I threw myself at the refugee crisis on the island of Lesvos in Greece in 2016. At the time, I felt like my prior experience acted as a springboard to get me to this point, but nothing could have prepared me for what I would witness over the upcoming twelve weeks. I arrived as an unaffiliated volunteer and I took my time in determining who the players were, what the nature of the refugee crisis was, and how this crisis was being dealt with on the shores of Lesvos.

Within the daily chaos and uncertainty, I managed to join a small kitchen operation preparing snacks and hot chai tea for the boatloads of refugees arriving on the Greek shores. This gave me time to process what was happening, it gave me some very raw interactions with people that had picked up and left their homelands in search of a safer home. Gathering information and settling in at my comfortable pace was something I normally prioritized when getting to a disaster zone, but it wasn’t as easy as it had been in the Philippines. It seemed like everyday I was being thrown off balance with new revelations of torture at the hands of smugglers in Turkey.

Smugglers in Turkey were operating recklessly, taking advantage of the mass flow of people displaced by war and cramming them in vans to be transported to the coastline surrounding the modern city of Izmir. These opportunists would then take payment ranging from 800 euros-2000 euros per person ($1200-$3000CAD) from refugee families to send them across a 10km stretch of the Aegean Sea separating Turkey from Lesvos. Their mode of transportation was usually an inflatable rubber dinghy fit for a capacity of 10-20 people or on occasion an older fishing vessel with the capacity for 30-35 people. More often than not, to capitalize on gains, the smugglers would manage to fit 50+ refugees on the rubber dinghies and 100-150 refugees on the fishing vessels. Crammed in like sardines, these boats would cross any time of day or night. Aided by a night-vision thermal camera we would scan the 50km stretch of Turkish coastline and try to locate boats making the crossing. This is exactly what I did for much of the next eight weeks, periodically checking in to the kitchen to see how they were doing.

Steps that we built into the landscape to make it easier to climb the west side of the rocky outcrop.

An example of a fishing vessel used to smuggle refugees from Turkey to Greece. This vessel was carrying around 120 people when it landed in the dark. The platform towards the back of the boat was presumably added by the smugglers to be able to fit more refugees on board. On occasion, boats similar to this would be too unbalanced navigating through rough waters and would capsize.

An almost identical boat to the other fishing vessel with a rubber dinghy in the foreground. These rubber dinghies accounted for over 90% of the crossings. Fifty people on average would be stuffed onto these dinghies, sometimes upwards of 100. As a size reference, the black box at the back is a 30 horsepower outboard motor

Our nightwatch station. Build from 100% recycled materials–from refugee boats. This is where we would scan the 50km Turkish coastline. The high vantage point provided less glare on the thermal camera. When it was our shift, we always made sure to have the essentials: the maritime radio, the thermal camera, a fresh batch of hot chocolate and cookies.

The Turkish coast guard intercepting a refugee boat, seen through binoculars.

But we would still try our best to clean up the giant environmental pickle that was in front of us. I’m cutting loose a backboard from one of the dinghies, we would build floors and tables with these inside the lighthouse buildings. The white boat behind me is a shoddy fiberglass boat that had around 20 people on board.

At the sight of a boat, we would use the maritime radio to relay information to the rescue boats parked at the harbour of Skala Sikamineas. Either the Greek coast guard, Proactiva or Sea-Watch would respond and escort boats to shore. If the boats were in distress, they would get towed to shore. If the boats were taking in water, refugees would board the rescue boat starting with women and children. Whatsapp was one of the main communication platforms to coordinate between and amongst the reception camps on the coastline. Everyone was pinging all the time.

Back on the coast, seeing thousands of people on the move seemed surreal to me. That surreal feeling came to a grinding halt one morning when a dinghy of mostly Afghan refugees came cruising in onto the rocky outcrop at the Korakas lighthouse. Six of us had just finished our night shift rotations. An English volunteer and I, dressed in full-body wetsuits were responsible for docking and securing the boat against the waves rushing in. The people on this boat seemed to be acting a little more erratically than we were used to. People at the front were motioning to the back of the boat. My Farsi, Dari and Arabic were practically non-existent, but amidst the confusion, the lifeless body of a young girl was being passed to the front of the boat. Her skin was almost white in colour and her eyes had rolled to the back of her head. The young girl was passed to a fellow Canadian volunteer who scrambled to grab a hold of the girl and bring her to shore to start administering first aid while yelling for our two Dutch medics who were at top of the rocky outcrop. Concerned about the girl’s life, I kept an eye on the shore and an eye on my task of steadying the boat for the other 50+ passengers. The girl was carried on top of the rocky outcrop so the medics could focus on their task at hand. This gave the whole team the ability to focus on their specific tasks. I am happy to say that the medics were successful in reviving the girl. Ten minutes later, she was jumping around outside with her other siblings unaware of what had just happened.

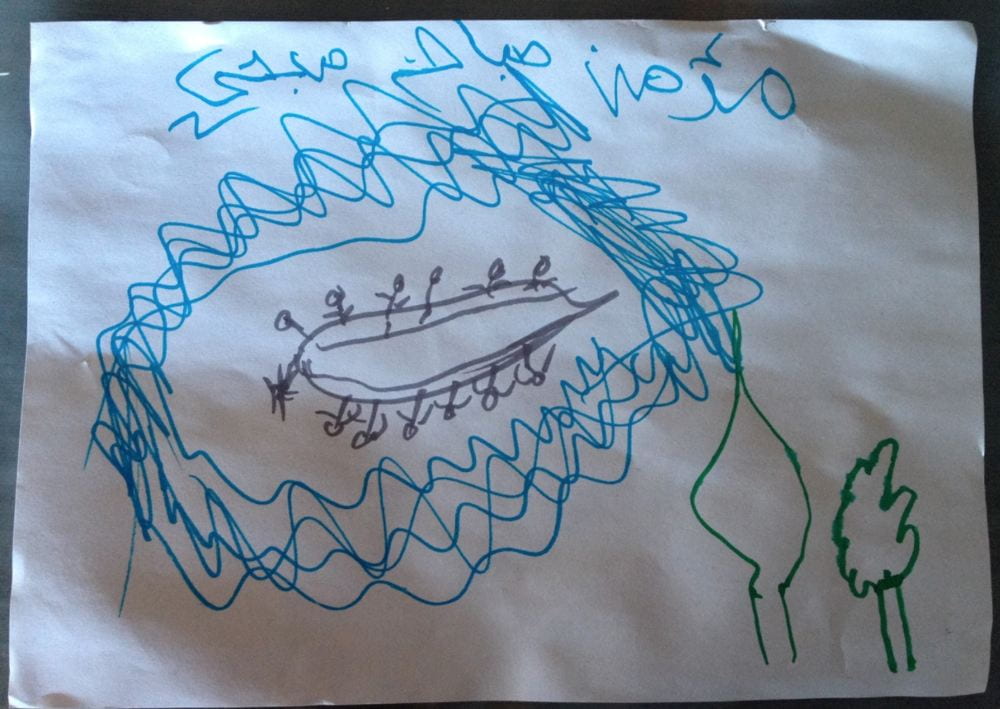

At one of the reception camps in Skala Sikamineas, a kids drawing table was set up to let kids relax a little after a treacherous journey. Sometimes the adults would partake and make a family affair out of it. A little girl drew this photo upon arrival, I’m assuming that’s her rubber dinghy and water surrounding it.

Heating up around a barrel fire after jumping in the Aegean Sea. This photo was taken ten minutes after the little Afghan girl was resuscitated. I was cold and stressed, but relieved.

Heating up around a barrel fire after jumping in the Aegean Sea. This photo was taken ten minutes after the little Afghan girl was resuscitated. I was cold and stressed, but relieved.

Heating up around a barrel fire after jumping in the Aegean Sea. This photo was taken ten minutes after the little Afghan girl was resuscitated. I was cold and stressed, but relieved.

Two of several passports we would find while cleaning the beaches.

Our team tended to several dinghy landings, some very smooth, some more chaotic. Syrians, Afghans, Iraqis, Iranians, Palestinians, Lebanese, Egyptians, Libyans, Tunisians, Moroccans and Pakistanis were all on the move. Some days would be very busy, other days would be very quiet, so we would begin cleaning the beaches of discarded clothes, discarded lifejackets, deflated rubber dinghies and boat engines. It was only in this cleanup process that I became aware of the quality of the lifejacket being given to the refugees for their crossing. They were fake. They were mass produced, likely for this occasion, with pop-up factories in Turkey. They were stuffed with varieties of packing foam in place of buoyant polyethylene foam. The jackets were not designed to float for very long under the weight of a human. But they were flying off the shelves in Turkey because they gave a false sense of security to an already perilous journey.

The highs and lows and the never-ending days on little to no sleep were very real here. The tumultuous nature of a refugee crisis makes every day interesting, however managing your feelings becomes increasingly difficult. Some days were laced with small victories, others days would be met with defeat by learning of a mass casualty at sea. One boat sunk, 25 deceased and 25 missing, or two boats missing, 10 rescued, 100 unaccounted for. This eventually got the best of me and I burned out. All along, I had always preached to myself to pace myself and take breaks when needed, but I didn’t listen. It was impossible to listen to that advice in this atmosphere, because for many of the refugees crossing, it was a matter of life or death. Volunteers understood this and many of us worked around the clock to match the intensity of the crisis we had thrown ourselves at. One cannot enjoy a latte under those conditions. An overbearing feeling of guilt would come over me every time I did something or acted in a way that wasn’t with refugees in mind. So what was my natural response? To leave Greece and go volunteer in a slightly lighter environment in Nepal.

We couldn’t clean quick enough to keep up with the number of arrivals. All of the black you see on the beach is rubber from deflated dinghies, the colour is either lifejackets or different colours of dinghies, with some fiberglass boat pieces mixed in and the odd outboard engine floating around. This was 100m of coastline and boats were landing across a 20km stretch of northern Lesvos. The seas were rough when this shot was taken, but boats would still cross. No deterrent for fleeing a war zone.

We would load discarded dinghies, bags of clothes, lifejackets and outboard engines on board dinghies and tow them to Kagia Beach, where a dump truck would them pick everything and dispose of the waste. Most of it was put in the lifejacket graveyard.

The loaded dinghies with mostly lifejackets.

A graveyard of outboard engines taken from rubber dinghies at the harbour police station in Mytilini, Lesvos. The scale of everything was difficult to comprehend, considering this was only a fraction.

This boat made it to the harbour in Molyvos.

Four key lessons I learned on the beaches of Lesvos:

- There will always be people ready to capitalize on misfortune. Not a very positive lesson, but one that is true. In natural disaster environments, this might take the form of violence and looting. In the case of a refugee crisis, a multi-million dollar network of smugglers from multiple countries were operating unrestricted across several borders. The demand was there and refugees were misinformed and sold these expensive transportation packages from smugglers. Many didn’t even make it to their intended destination and I hope they can now rest in peace. This brings me to my next lesson.

- Sometimes important stakeholders turn a blind eye when the going gets tough. The lack of a common goal amongst EU members meant that the EU response was fractured and not in line with the interests of the refugees. Truth is, this requires a real paradigm shift. Communities and cities of wealthier countries have to be willing to share. This means sharing their community, sharing their wealth and understanding that people that have come from the depths of a war-torn country frequently become some of the most productive members of the societies they embrace. It is deplorable that a safe passage across a dangerous body of water cannot be negotiated for stateless people when I can pay fifteen euros for the exact same crossing, by virtue of my Canadian passport.

- Always listen to yourself. This is hypocritical for me to write, but I would like to think that I have learned from my experience in Greece. Burning out accomplishes nothing. Pace yourself and take breaks when needed. This is not a weakness, this is a strength. After you move on from such an intense experience, make sure you have time to debrief with supportive people and give yourself time to decompress. I cannot stress this enough. Skipping this step will haunt you.

- You choose your passion. I had an instant draw to disaster zones. The fast-paced unpredictability mirrors much of my work experience and is excellent for calm, level-headed people. Choose your passion, choose an organization that operates in line with your morals and dive in. If your passion is knitting, then knit as hard and with as much passion as you can. If your passion is Snapchatting, find a new passion.

Patrick McBride, Guelph IDS graduate (2011), reflects on his life in multiple disaster and crisis zones in the Philippines, Greece, Nepal and the United States over the last four years. In this six-part series, Pat shares his unique experiences rebuilding homes and hope in some of the worst crises of our century. If you have questions for Patrick, he can be reached at patrick.mcbride01@gmail.com, or follow his adventures on Instagram: @sea.nugget