After my first disaster response project in the Philippines, I had to return. So I did. Six months later I was looking out the window on my Japan Airlines flight, equipped with a brand new appreciation for my degree and how it helped me navigate the intricacies of a disaster zone. This second project was in response to Typhoon Haiyan and I was arriving eleven months after the storm. Haiyan was one of the most powerful storms to ever make landfall in the Pacific. Wind gusts of 300+kph coupled with a twelve foot storm surge in much of the greater Tacloban City area meant that much of the critical infrastructure, vital to the functioning of a city, got levelled.

The unwillingness of the government to release an accurate official death count was enough evidence to suggest that there was a degree of embarrassment surrounding the lack of a preparedness plan before the storm. Several accounts from locals suggested that mass graves were plenty and they were disorganized. This would later contribute to an issue of water contamination in the area.

We were warned of potential cholera outbreaks at some of the sites we would be working at. Amongst them was a pop-up emergency shelter site funded by the International Organization on Migration (IOM) and Samaritan’s Purse. Many issues that we encountered with transitional-type shelters or emergency shelters, were with poor drainage of already low-lying sites. These drainage issues were ones that transpired over the course of a year, and became a focal point for our project. Something like water drainage, which goes overlooked in the immediate aftermath, was quickly creating risks of infectious disease outbreaks. This cascading effect is what keeps INGOs and NGOs busy for many years after an event like Haiyan. As proactive as actors would like to be in the field, combating the cascading effect quickly give projects a more reactive tone.

This was the size of a room which was supposed to fit a family of 4-6 people. Many would dedicate part of this space to opening a shop to sell snacks and beverages, leaving less livable space.

The walkway at one of the bunkhouse sites. No privacy.

Poor drainage at one of the bunkhouse sites meant that contaminated sludge was under their floor boards.

An example of one of the 100+ transitional homes at Cabalawan. A 4mx4m footprint complete with a little porch, a cooking station on the inside and storage space underneath the home.

Digging a network of gravity-powered drainage canals through the clay at a transitional housing site called New Kawayan.

A before shot of the Cabalawan build site. This was a rice field converted into transitional housing site.

The transitional shelters of Cabalawan complete with a multi-purpose hall in the foreground.

Aside from the enormous task of resolving drainage issues across numerous transitional housing sites, the project was on its upswing at a build site in Cabalawan, fifteen minutes north of Tacloban. We were well into the build, having completed over one hundred transitional houses on this IOM-funded site. The United Nations Development Program (UNDP) was active in supplying materials for the build and Samaritan’s Purse was responsible for overseeing the build of the washing facilities. Six weeks into the build, we were notified that a super typhoon packing winds in excess of 250kph was headed our way. We gathered all the rope we could get our hands on and tied down the roofs of the bunkhouses where all the displaced people from Typhoon had been staying. Last item on the checklist was to board up the windows in our compound, lay down sandbags and move everything out of flood water range. On the seventh week, Typhoon Hagupit made landfall on the eastern coast of Samar, the neighbouring island to the east. It was an experience I will never forget. I never knew wind could make such noises. I feared for the community outside our concrete compound. Not everyone had access to shelter that would outlast the power of Hagupit. Waking up the next morning to knee deep water in the driveway, surrounding roofs peeled off, palm trees all windblown and the streets silent was quite sobering. We did a quick drive-by of the several bunkhouses we secured with rope, and found all the roofs intact. It had worked. Without missing a beat, we got straight back to work loading food aid onto dump trucks.

Within two days after the storm, I joined the disaster assessment response team in Western Samar. A symptom of the immediate post-disaster atmosphere is overcrowding at the worst hit areas. Media, INGOs, NGOs all seem to congregate around the epicentre with no real attention focused on the immediate proximity. After our assessment of a village called Calampong which was in this proximity zone, we were going to have our work cut out for us. Calampong had just 680 inhabitants. Land access was virtually cut off even though the village was on the mainland. Calampong was heavily reliant on boats for not just their fishing industry, but for a taxi service to a more serviceable part of the mainland. And so we helped fix their boats, and slowly as we began to gain the trust of the community, we built their traditional Filipino banka boats from scratch. This bred a unique fundraising idea for a fellow English volunteer by the name of Graeme and I to build a boat from scratch without any assistance, and paddle it 120km over four days from our major base in Tacloban to our new satellite base in Calampong. We named our boat the SS Bubble Hunter. That name came about from a funny episode where one of our team members convinced another one of our team members that the bubbles inside of a spirit level could be sold separately from the little capsules where the bubbles are contained. This team member then spent the better part of a morning in Tacloban doing their best to explain in English to hardware store employees that they just wanted to buy the bubbles and nothing else. After an apology and much laughing, this gave life to that name.

Fifteen days later, our boat Bubble Hunter set off from the Tacloban coliseum. On a journey that led us through a rainstorm and some choppy seas, I am proud to say that the boat did not spring a leak and we did not need our flotation devices – click here for a video of our adventure.. There was one small incident where we were camped out for lunch on a little exposed rock shoal in the middle of a bay and Bubble Hunter floated away on us when we had our backs turned. I was not very keen on jumping in the water and swimming one hundred meters to go rescue our vessel given the amount of venomous water snakes we had seen, but I also did not want to be the next Castaway. This journey to me, embodied the spirit of volunteering. It was the ultimate test to gain the trust and the approval of Calampong, and I would like to think that it was a success. One day after landing on the shores of Calampong, I had to say goodbye to the Philippines once again, having served for twenty consecutive weeks between Tacloban and Calampong. This was a particularly difficult place to leave. I often think back to the residents of Calampong, they were the happiest people I had ever met.

Four key lessons that I learned on Leyte and Samar:

- With the right attitude, and the right spending habits, donation money goes a long way. A lot of focus is placed on wasteful spending and lavish accommodation amongst some of the larger INGOs. I cannot speak to this. I can however speak to the efficiency of spending when an organization values every dollar of its donation money, because I’ve seen it over and over again. Using crammed local transportation, hiring local drivers, hiring local cooks, hiring local carpenters/masons/boatbuilders, hiring local logistics managers and sleeping in tents or large communal areas are all indicators of resources well spent.

- Best practices are developed on the fly. You can have a protocol to follow or a set of guidelines, but ultimately, the flexibility of being open to learning and adapting will always win the day in disaster zones. This is especially the case in the volunteer community where people come and go. You will attract professionals that have twenty years experience in human resources, or logistics planning, or education that offer up excellent advice to make the project run smoother. People come from all walks of life and offer different perspectives that perhaps the development community could use and learn from.

- Your actions have the power to speed up a community’s recovery time. The more time I spend in disaster zones, the more I trust the power of softer approaches to make the biggest impact. This could be as simple as listening and empathizing, participating in community gatherings or organizing community sporting events. Of course harder approaches such as aid, building medical facilities and building schools will help the recovery time, but it is the manner in which it is delivered that can be the wildcard difference maker. Here is an article on the significance of our volunteering.

- Trust is everything. Particularly during the boat building phase, the need for community trust became apparent. Letting a stranger into your home requires a degree of trust, letting a stranger into your home when your community is only 680 inhabitants requires several layers of trust. A longer-term presence, coupled with a locally-hired translator set the stage for trust to be built, but ultimately what made the biggest difference was this- being vulnerable. It was extremely uncomfortable at first, but being the visitors, we needed to provide them with something first before hoping to get a response. We provided them with vulnerability, and the community reciprocated. As soon as trust is established, projects really come to life.

Secured the outriggers, ready to set off from the Tacloban Coliseum.

A cargo ship we encountered in the San Juanico Strait. The currents that morning were pulling us in every direction.

Two locals we ran into on Jurassic Park Island (Bagatao Island) that cooked a meal of freshly caught squid and snails for breakfast.

The two young men then led us on a hike to the top of the hills on Bagatao island where we got an incredible view of the greenery from above.

Graeme and I leaving Jurassic Park Island (Bagatao Island) on our last 12km stretch to Calampong. I’m doing a T-Rex and it looks like Graeme is a pterodactyl. Well played, sir.

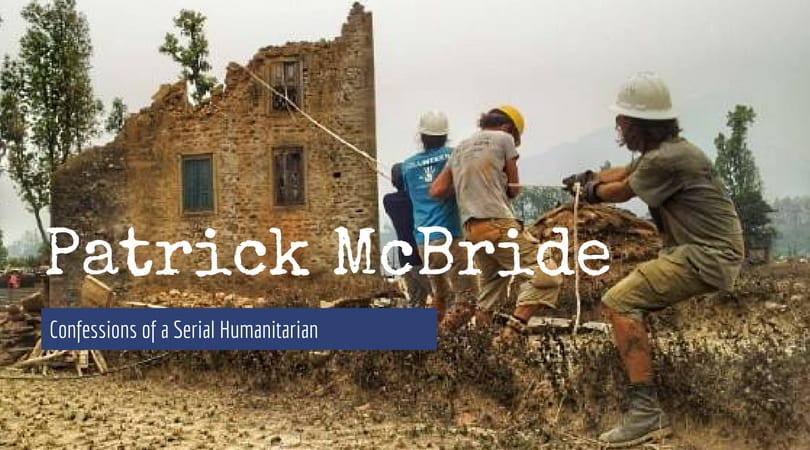

Patrick McBride, Guelph IDS graduate (2011), reflects on his life in multiple disaster and crisis zones in the Philippines, Greece, Nepal and the United States over the last four years. In this six-part series, Pat shares his unique experiences rebuilding homes and hope in some of the worst crises of our century. If you have questions for Patrick, he can be reached at patrick.mcbride01@gmail.com, or follow his adventures on Instagram: @sea.nugget