Going straight to Nepal from a mentally taxing experience in Greece was a poor decision in hindsight. I left in a rush, with plenty of unfinished business that needed taking care of. It was a fight or flight response and ultimately, to preserve my sanity, I fled. The decision didn’t sit well for a long time, but there had to be an end in sight and leaving at the end of my visa seemed like a good natural end point. The decision was made—I would be joining a mobile demolition team roaming the Nuwakot region of Nepal.

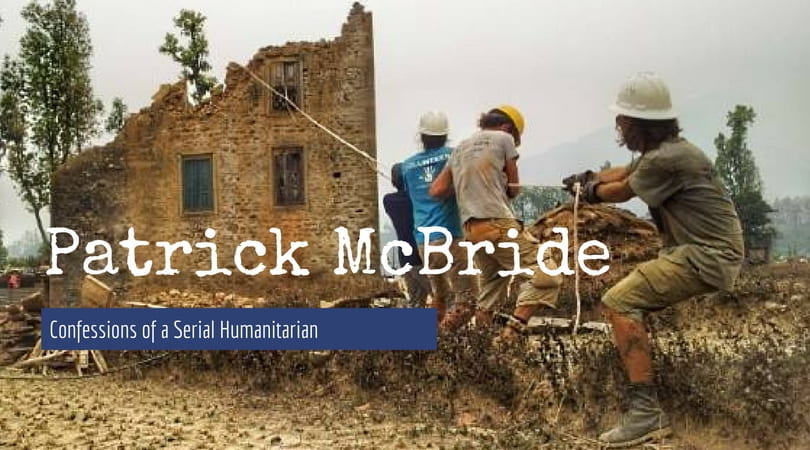

Our primary mission was to create a demolition program that was widely recognized in the disaster response community. The Nepali army was the main body responsible for demolition after the earthquake, but with little direction and experience in demolition, some accidents that they suffered caused them to pass on some of the responsibility. We stepped in and our crew of eight began to tackle some of the more challenging demolition projects in the rural parts of Nuwakot region.

Going straight to Nepal from a mentally taxing experience in Greece was a poor decision in hindsight. I left in a rush, with plenty of unfinished business that needed taking care of. It was a fight or flight response and ultimately, to preserve my sanity, I fled. The decision didn’t sit well for a long time, but there had to be an end in sight and leaving at the end of my visa seemed like a good natural end point. The decision was made—I would be joining a mobile demolition team roaming the Nuwakot region of Nepal. Our primary mission was to create a demolition program that was widely recognized in the disaster response community. The Nepali army was the main body responsible for demolition after the earthquake, but with little direction and experience in demolition, some accidents that they suffered caused them to pass on some of the responsibility. We stepped in and our crew of eight began to tackle some of the more challenging demolition projects in the rural parts of Nuwakot region.

An example of one of many homes that we had to demolish in Kagati, made from stones and mud mortar. Throughout the demolition process, we had to watch out for venomous snakes in the walls between the two sleeves of rock.

The humble little blue tent where our mobile demo team slept. This was taken in the village of Kalika in the foothills of the Himalayas where we demolished their damaged school building.

We built a ping pong table at our base because you can’t work hard without playing equally as hard.

The main focus for our team ended up being a village by the name of Kagati. Even though it was just over the ridge from the Kathmandu valley, many Nepalis I spoke to had never heard of it. We slept on the floor at a health unit at the top of a ridge with a helicopter pad conveniently placed a few steps from our front door in case of an emergency. Being at the top of the ridge provided us with a stunning view of the surrounding valleys and the swarms of eagles coasting and taking advantage of the thermals created by these landscape features. Kagati was what we termed an ‘ODC’ or an open defecation community. From what I saw, Kagati had been forgotten. The footpath we would take to reach our sites during the day was littered with human feces. The lack of wash facilities in Kagati meant that people did what they had always done. Popped a squat whenever and wherever they felt. You can imagine, many of us got very sick. Kids with raggedy, torn t-shirts running around barefoot, playing alongside chickens and pigs, machetes in hand, snot running down their faces, unable to wipe off the perma-smiles while engaged in full-bellied laughs. That is the image that I have decided to keep of Kagati.

Even though I was very dedicated to the project in Nuwakot, my mind was still on the beaches in Greece. I was not always fully present, daydreaming of the lighthouse at Korakas and the friends that witnessed the intensity just as I had. Eight weeks on project and my time came to a close, but I was determined to give Nepal another chance. So I booked a return flight to ensure that I would.

Five months later, the atmosphere of the project had changed so much. Not only that, but my mood had changed substantially, having time to let go of the things I couldn’t control about Greece. I returned to the Nuwakot region where a full-scale school rebuild program was gaining traction. The community of Ratemate (meaning: red mud) welcomed us in. I had been here once before, having demolished their old school six months prior, so this was my chance to reacquaint myself with all of the familiar faces of the tiny hillside community. Our base was a functional camp of various bamboo structures and canvas tents spread across three rice terraces overlooking the valley of Trisuli. We were surrounded by dense teak forests and rice paddies. The name of the school we were building was Bachchhala and the mood at Bachchhala was never dull. It was a microcosm of eager volunteers from all reaches of the globe, uniting on this one man-made terrace, putting their skills to the test and learning new skills along the way. I spent the majority of my twelve weeks in the woodworking shop we had made. I was leading a carpentry team to build various sizes and shapes of formwork to allow concrete to be poured into our casts, making the skeleton of the two school buildings.

Once every morning we would all break for some chai tea and biscuits, giving us an opportunity to exchange quirky little phrases with the Nepali masons, who were the engine behind the whole operation. They would jokingly yell to us: “why no working?”, keeping us on track for the build deadline. We would respond: “kina kaam nagareko?” which is the rough Nepali translation of the same phrase. This always kept the mood jubilant. Once a week for an hour, our community relations coordinator would host a Nepali class for volunteers and during that same time period a volunteer would exchange the service and host an English class with the masons. To practice my Nepali, every time I would drive in a four-inch nail to secure our forms, I would count each swing of the hammer in Nepali. “Ek, Dui, Tin, Char, Panch, Chaw, Sat, At, Naw, Dos”. Dal Dai and Deepok Dai, the two masons I worked with consistently would always crack a smile, then crack on with their work. They both had such incredible patience. Being unfamiliar in working with crooked wood and poor quality nails, as I was, they showed me their best practices, and I was happy to try my best at duplicating. Their work is what made the program work with such ease.

Another engine behind our progress was Aama (Netra), an elderly lady in her seventies that donated the land so that we could build a school in her backyard for the community’s children. Her house was very basic with mud floors, flimsy wooden walls and a corrugated tin roof. She tended for her goats and would frequently be wielding a machete like the best of them. Aama always had a fire going in her kitchen with fresh chai. She would visit us daily on site with a jug of water, and would frequently pick up a shovel to get involved. Aama wanted to pay it forward to the future generation with her generosity. Instead of cashing in on her land, Aama chose more noble pursuits and provided the conditions under which education could flourish. Whenever I’m confronted with a challenge, I always think to myself, what would Aama do? And then I do that.

I decided that I couldn’t leave Nepal without being in the Himalayas. I had been in this country for a combined twenty weeks, had seen the white-capped mountains through the clouds on occasion, but had never gotten close to them. I wasn’t feeling particularly burnt out this time, but burn out shouldn’t be a precursor for taking a break, so I told myself that Aama probably would. I went ahead and took a bus trip to the trailhead of the Langtang Valley trek which at its nearest point is less than five kilometers away from Tibet. This experience was wonderful, especially since I was quite tunnel-visioned on the success of the project, I never really stopped to enjoy the fruits of the country that I called home. On the second day of the trip, I celebrated my birthday by having a Kit Kat bar. This was a rare and expensive indulgence in the Himalayas since most supplies had to be brought in by porters or by horseback. On the fifth day of the trek, I crossed over the village of Langtang which had been buried by a rockslide during the earthquake of April 2015. It was upsetting walking over the rocks because on the map application I was following on my phone, somewhere buried ten feet underneath me was supposed to be a bakery, a police checkpoint, a guesthouse. On the seventh day of the trek, I wished my mother a happy birthday in a video I took at 4000 meters above sea level with some yaks. I got very up close and personal with those yaks which probably appreciated my long hair as much as I appreciated theirs. On the eighth day, I essentially trekked the distance of a marathon mostly downhill to get back to the trailhead because my flight was the next day. This time, I didn’t book a return flight.

Aama’s house on the perimeter of the build site.

Setting the formwork for building #1. These forms were for the beams to support the floor of the second storey.

The woodworking shack where all the formwork was built. We had to tackle frequent power outages, but at least we were out of that sun

Weaving that intricate web of rebar to ensure maximum earthquake proofness. We would then pour several hundred tons of concrete on top of the rebar grid and give it two weeks to set. All the formwork was coated in engine oil make it easier to peel off the forms when the concrete had set.

Four key lessons I learned from the hills in Nuwakot:

- Sometimes, words just won’t do it justice. I have tried many times to explain to friends and family the intricacies of disaster zones and the roller coaster of emotions that nobody prepares you for. This was especially the case trying to explain my experience in Greece to fellow volunteers in Nepal. The reality is that they were not there. No matter how hard you try, they will have a hard time understanding the information you are throwing at them. This is not their fault as much as it is not your fault. I have coped with this by breaking down my experiences into bite-sized pieces of information that are easy to grasp. Keep your most prized memories for yourself.

- Relax, you’re fine. There is good chance that you, yes you reading this right now, are better off than over 80% of the world right now. I was always aware of this through traveling and other volunteer projects but this was hammered home in Kagati. Whether it is access to education, access to wealth, access to health, access to opportunities, access to technology, you are better off than most of the world. You most likely have a toilet to use at your leisure, you most likely know where your next meal is coming from and you don’t have to worry about contracting some water, food or mosquito-borne illness.

- Be like Aama. Aama will always be a source of inspiration in my mind. Most of the people reading this won’t know about Aama beyond what I have described, but that’s ok, because you might have had an Aama in your life at one point or another also. Without using words, she taught me some very valuable lessons in generosity and humility. Be a rockstar, just like Aama.

- Control only what you can. A source of community friction in Nepal was surrounding the caste system that was still deeply ingrained in rural parts of Nepal. In a perfect world, communities members would all recover equally to their pre-disaster state. Unfortunately, we do not live in an equal world. The challenge with this project was making economic opportunities in the community available across all castes. Remaining sensitive to the community’s method of organization while providing impartial assistance is a difficult line to toe.

Patrick McBride, Guelph IDS graduate (2011), reflects on his life in multiple disaster and crisis zones in the Philippines, Greece, Nepal and the United States over the last four years. In this six-part series, Pat shares his unique experiences rebuilding homes and hope in some of the worst crises of our century. If you have questions for Patrick, he can be reached at patrick.mcbride01@gmail.com, or follow his adventures on Instagram: @sea.nugget